The Art of the Signature

November 10, 2024

As I sifted through the onslaught of post-election stories, one headline jumped out:

Nevada votes thrown into chaos because young voters can’t sign their names

Apparently, some 13,000 mail-in ballots were rejected because signatures, as required by state law, did not match between the ballots, the system and/or on driver’s licenses. That would be a hell of a thing to have your vote nullified because you can’t settle on a signature.

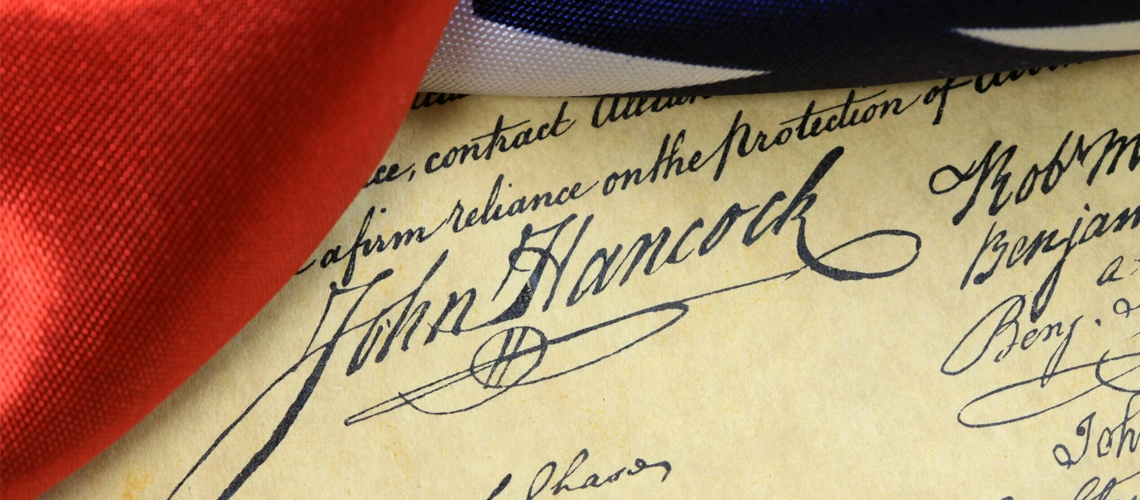

John Hancock’s signature on the Declaration of Independence is arguably the most famous political signature in our nation’s history. The story goes he made his mark big and prominent not because of his political stature but rather so King George could read it without spectacles.

But signing one’s name distinctively may be a lost art. According to The Atlantic, “There was a time when we took our signatures seriously, when we believed they said something about who we are. But now we have PIN numbers.” Others notice that, “Simply holding a pen is becoming an alien concept for many children.” Is it any wonder then, as Marianka Swain writes, the death of the wet ink signature is “a depressing sign of the times”?

I did an economics lesson with my high school freshmen years ago asking them to sign their names on a blank sheet of paper. Some used flowers, hearts, or smiley faces to dot their “i”s, some wrote in puffy or block letters (remember, none of my students have ever received cursive writing instruction in the public schools), and nearly all of them created something akin to a ransom note collage with different sizes and styles of letters rotated haphazardly along a rising or descending path. Befuddled, I asked, “How are you ever going to sign a paycheck?” I received a universal response of shoulders shrugging to ears and a mumbled “I don’t know.”

I can remember when and why I settled on my current signature. Some of you will laugh, especially those who know me best, but I’ll tell the story anyway.

I was 18 and playing summer baseball. Like many young athletes, I thought I could make it to the show, conveniently ignoring physical deficiencies more discerning eyes (aka, scouts) picked up on early. Still, I managed to have a good high school career that extended into the summer before college and it was then that my current signature came into being.

During a game at a city playground, I hit a home run. I hit more than my share so there really wasn’t anything special about this one. It didn’t break/tie a record and it didn’t win a game; it just sailed over the chain-link fence in left-center field and I jogged around the bases (Note: there wasn’t much difference between my “jog” and my “sprint,” something those aforementioned eyes knew all too well).

As I was sitting on the bench putting my catching gear on a young kid (I guess, 8 or 9 years old) handed me a ball and said, “Can you sign this?” It was my home run ball. He had gone into the woods beyond the fence and retrieved it. I said, “Sure,” thinking this first one wouldn’t be the last (spoiler alert: it was) so I took the pen from our scorekeeper and signed.

I signed in the only manner I knew how. I had learned cursive, to make every letter distinct and well-formed. The letters in my first name were connected as were the letters in my last. I don’t have a long name, but it took forever (aka, I write like I run) as I meticulously crafted easy-to-ready letters that stretched too far around the ball. As I handed it back to the kid, I realized just like with anything I needed to practice to become a better signer of the ball.

I had extra baseballs. I had a 5-gallon drywall bucket filled with old baseballs that I used for throwing drills. I would start at the cutout behind the pitcher’s mound and throw 15 balls into the backstop behind home plate. Then I would move back to half-way between the mound and second base and throw 15 more, then to second base, then the outfield, and continued backing up until I had thrown 100 balls. These balls became my canvas as I perfected the art of my signature.

I wish I could show you the transformation, but online privacy dictates I don’t put digital scans of my signatures up on the intraweb. Suffice to say my final rendition was a marked improvement over the original. The “J” and “P” were full and round, the “o” and the “a” were somewhat readable, but then the rest of the letters slurred into nothing more than a squiggle. It was perfect; quick, unique, and I jotted it down on job applications, replaced my original driver’s license sig, car loans, student loans, mortgages, paychecks… and yes, my voter registration. There was no question it was my signature on my voter ID at the polling station; it was identical to the one on my license and everything else I’ve signed since my 18th summer.

Maybe we can unlock our phones with finger and thumbprints, and maybe in movies doors are unlocked with retinal scanners. I still think it’s important we cram in a lesson or two on the importance of a personal signature. I know high school curriculums are full, but we’ve got two years before the next election. That should be enough time.

Picture courtesy of the Alabama Political Reporter 2024